Rethinking Developer Infrastructure

Moving beyond ecosystem forks: A unified approach to caching, testing, and automation

I've been tinkering in some of my coding time at Tuist with what a solution with great developer experience would look like to solve the need for optimizing workflows (build, test, and custom automation), which is becoming more and more pressing as AI agents write more code to support development.

Traditionally, teams resort to bumping the environment spec—for example, with beefier CI environments and developers' laptops—which places the focus on the container while disregarding the content, likely because of a short-term mindset. It's easier to just throw money at hardware and kick the can down the road, but sooner or later you find yourself in a position where you can no longer ignore the content. We see this at Tuist with Xcode projects. I experienced it at Shopify when they decided to transition from native mobile development to React Native, and most recently I've seen them starting to invest in building developer tooling with Nix at its core. At the time I was there, they also spun up a test infrastructure team to be selective about which tests they'd run and mitigate the flakiness that would cause slow retries and prevent them from shipping faster.

Strategically, prioritizing solving the problem in such a generic manner is a bad idea for the business, which is why we're considering stepping into ecosystems closer to ours as our next steps—like Android and infrastructure—without which we can't build the level of performance that we want our users to have. However, and this is a bit of my personality, I like playing with what a different future might look like, thinking about a potentially better future, and building a path backwards to the present. As part of this exercise, there are a few patterns we've noticed, a few ideas about how the space might evolve, and how that developer experience might look. All this experimentation is happening at Fabrik, which is a bit of a materialization of my experiments. The experiments there gravitate around the following ideas:

Key Observations

All build systems will have caching capabilities, and alignment on the details of the contract is unlikely. Companies that adopted Bazel might consider switching back to the native toolchain, reducing their maintenance costs significantly and helping advance the official toolchains instead. Bazel remains ahead in terms of capabilities, but it's an ecosystem fork, which helps with innovation but makes it inaccessible for many organizations.

Build systems' caching contracts will leave many details out, like how to secure the interfacing with the systems necessary to distribute the cache, or attribution of the interactions to users or projects. These details, left out by build systems, will be crucial for companies who care deeply about security or want to have deeper insights, like cache effectiveness per environment. Companies providing cache as a service that go this extra mile will be solving the same problems for every build system, duplicating efforts unnecessarily.

If caching capabilities materialize, then the network latency and bandwidth between the machine and the cache become more important than the machine spec itself, since a warm enough cache will result in most build operations becoming I/O operations. This is an interesting future for us because it means we don't need to deploy machines ourselves and can instead lean on big players like AWS that have everything figured out around how to colocate instances and ensure the routing between them is as fast as it can be.

The CI runners space is already getting crowded, and it'll get even more crowded since it's a replicable business model, which will push some players to move vertically and aim at providing new solutions—likely caching and potentially other build or test-related solutions. This is where things get interesting, and where I want to talk more about Tuist. I was reading the other day an update where someone mentioned partnering with AWS to give a workshop on how to use EC2 machines as runners, and I couldn't help but think about how much of this reality is already happening.

Developers don't like when service and technology are the same thing, or are somewhat strongly dependent on each other, like Next.js & Vercel, which for many years had internal designs that gave Vercel an advantage over competitors. It's a fine line to walk, where if you walk it well, you can have Vite (commodity) and Vite+ (service), or you can have a company that's struggling to put their proprietary tech into the hands of users.

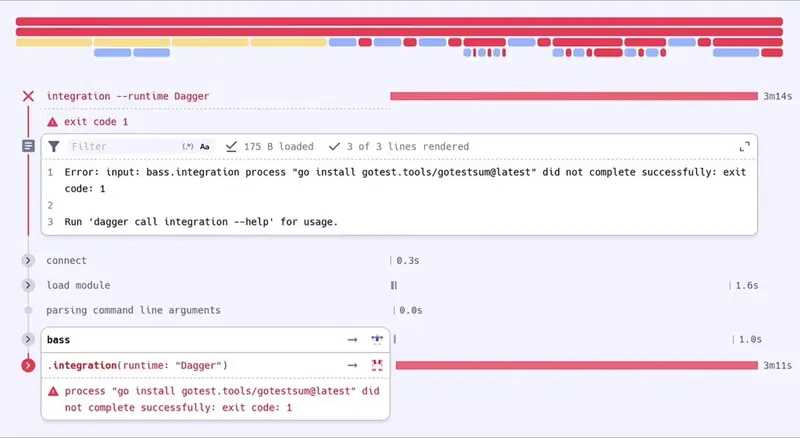

Forks are costly. Bazel is a fork. Dagger is a fork. Forks bring innovative ideas, but it's a huge risk to build a business on it because many companies will see the investment as a liability from the get-go, so you have to convince them the investment is worth making. Tuist's generated project is a fork of Xcode project, which we'll hopefully be able to move away from at some point, but at the end of the day, you get a standard Xcode project, so it was easy for us to remind organizations that this is not a liability. Any investment that we make has to be incrementally adoptable, and we should embrace what people use every day, with their flaws, even if we disagree with the design—like YAMLs for CI pipelines, or the fact that runners as a service is a trend you'd better align with.

Tuist's Strengths

One of the things that Tuist does great, and which I'm very proud of, is its community, which took years of nurturing and building, our openness, and our taste for great developer experience. Since its inception, it has gravitated around the Apple ecosystem, mostly reverse-engineering their tools and accidentally building a moat that helped us get the business off the ground.

The Fabrik Experiment

So I created a repo, Fabrik, and started playing with the idea of separating automation tools like scripts, test runners, and build systems from the infrastructure that gives them extra capabilities, in the same way shipping containers separated the goods being delivered from the means of transport. Initially, I placed a focus on caching, but as I kept coding with the help of agents, it became more and more obvious that a technology should span across build systems, test runners, and custom automation (e.g., scripts), and give teams visibility over how those tools are performing, along with optimizations to ensure they'd do the most efficient job possible. This is where the infrastructure would come in, but more on this later. A technology that, like shipping containers, would solve the fragmentation—something I don't expect to change since every tool lives within its own ecosystem, and while there is some alignment, it's not as widespread as many would like it to be.

Authentication and Developer Experience

The first idea I was playing with is: can we move from a "one token for everyone" model to a system that's able to require me to authenticate to access the cache and activate the right configuration, no matter which build system I'm using? Turns out it's possible, and a local proxy with a mapping from project directory to port, plus a hook or command to activate the server, can lead to a pretty great developer experience. Your project just requires a fabrik.toml file, and voilà—you'll be able to just cd into a directory and interact with your project with cache enabled for you, magically. I played with Turborepo, Bazel, Xcode, Metro, and Gradle (have more on the list) and got all of them working. Some can only be configured via configuration files or arguments passed at invocation time, but I'm thinking about starting conversations in those repositories to change that. It's likely that they never thought about that as an opportunity to improve the developer experience.

As I was working through the build systems, I noticed how all the APIs were very similar semantically, but the conventions differed, which made me think about how cool it would be to unify the contract beyond the local layer so that one doesn't have to implement the contract of every build system. This naturally led me to fabrik exec as a wrapper to activate the environment on the fly, instead of doing it using shell hooks when entering or leaving directories. Thanks Mise for those awesome ideas. You continue to be amazing!

Caching Scripts

From there, I paused and started looking at Nx (talking about companies who mix technology and service), and once again learning from Mise, I thought: why not bring caching to scripts? I couldn't help but think about those GitHub Actions cache steps whose artifacts can't escape CI. It didn't feel right. If CI has done npm install and resolved dependencies, can't I just pull those and skip the resolution phase and pull them from very fast storage? This is the premise of Nx, which went from a task orchestrator for the JS ecosystem to a task orchestrator for any platform (likely to match the expectations that came with their investment). Can this be simpler? Turns out it can! I'll throw in an example here that speaks for itself:

#!/usr/bin/env fabrik run bash

#FABRIK input "package.json"

#FABRIK input "package-lock.json"

#FABRIK output "node_modules/"

echo "Installing dependencies..."

npm ci

That's it. Your installation of dependencies is cached—on CI, locally, and in agentic environments. Instead of creating a new configuration file to declare caching attributes of existing scripts, you can just use annotations in the script, and Fabrik will take care of the rest. It was crazy that this implementation just took me a few minutes with the help of agents and replicates a big portion of the value that Nx provides.

Build System Integration

Things started to get interesting. What if Fabrik could also be a library that build systems could directly integrate, either by importing it via a foreign C interface or by directly invoking a CLI interface for interacting with the cache? Suddenly tools could bring caching capabilities without having to reinvent the interfacing with the infrastructure, which would be designed to accommodate multiple backends. So there I went and coded a C interface, which is distributed in every release as a static library that they can link. We could eventually make Tuist's module caching and selective testing just plug into it and delegate a big chunk of the responsibilities to Fabrik.

Authentication Flow

As next steps, I want to explore what authentication can look like in this world. Early thoughts led me to OAuth2 Authorization Code flow with PKCE so that the user can be taken through a web-based authentication workflow, and then an access and secret pair is persisted and managed by Fabrik automatically, ensuring that if refresh is needed, it does so while accounting for the concurrent nature of the requests. The caching layers needed for low latency and high bandwidth can then validate the token without having to go to the server, which would have a high penalty on latency—precisely something we want to avoid. Thanks to this, we can add attribution data as well as environment data to the interface of those layers so that any service using the technology can augment data such as hits or misses with things like which environment the data came from or at which layer the hit resolves. Also, if the person leaves the organization, even if they took the access and secret keys, they won't be able to renew the session if expired.

Two Key Directions

From there, there are two directions that I'd like to explore.

1. Layering of Caching

The first one is layering of caching. Build systems with CAS need the cache to have the lowest latency and bandwidth possible to get results. Unlike running the operations locally, which has CPU cores as a ceiling, network presents more parallelism, but if latency and bandwidth are not great, then the build times might end up being slower or not as great—especially in build systems like Xcode's that have not yet been optimized for remote caching. This is where the companies that either provide CI or runners for CI have the moat, because they can colocate runners and cache machines. Hence the strong appetite for solving cache that we're seeing in them.

We're going to take a different approach—one that works no matter where your builds are running from: locally, on CI, and from agentic environments. This requires two things: first, a technology (Fabrik) that's designed for this, and managed infrastructure that can run the technology closer to where it's needed. This, conceptually, is not new. Supabase can manage a PostgresDB where you need it and manage replicas too, and Vercel can run your functions close to where they are needed. There's a caveat with the Vercel model that many don't realize, and it's the fact that any win in reducing latency because it runs on the edge usually gets diminished when you have to go all the way to another region to hit a database. Think of Fabrik managed by Tuist as cache on the edge with a nice developer experience where you can choose where you need the caches, and why not, deploy some in offices or enable P2P sharing of binaries within the local network of the office. Some companies kind of do something like this for large enterprises, but it's not productized. It requires huge investment and a lot of engineers dedicated to a single tenant for weeks to get this up and running. Deploying a Fabrik cluster should be as easy as clicking a button on a UI, and plugging into it should be as easy as installing the CLI and logging in. This is where we need to be.

2. Testing and Telemetry

The second area I'd like to explore is testing and telemetry. In this case, the low latency and high bandwidth design requirement is not there, but there are some common needs, like test selection and flakiness tooling, that are once again solved over and over, either in-house or by third-party vendors. How much of that can be separated from the vendor, who could focus on the UI layer to interface with the solution? No idea at this point. I even wonder if Fabrik should just be about caching, but can't tell until I explore it further.

Telemetry is also something teams need. In the same way you can monitor what's going on in your remote servers, I think you should be able to do the same with build and test runs and custom scripts. Something that can go from the simplest—which is having the standard output and error of those environments, which is enough to run some diagnostics—to something more structured using real-time data as build graphs are processed by the build system. In this area, I think Dagger Cloud has done an amazing job providing a visualization tool for the execution of their DAG, and we should learn from there. Again, not sure if this is a Fabrik thing, but I'll explore and see. Fabrik might act as a standardization layer and maybe plug itself into build systems and test runners at runtime so that the information is streamed to the server live.

Looking Forward

I haven't been this excited in a long time. Shaping Fabrik reminds me of the early days of framing Tuist. The more I dive into other build systems and bring the best DX from around, the more confident I feel that the technology and service split is the way to go, and that we need to step into infrastructure to make the DX that we want to provide a reality. While our main customers will remain large enterprises, we want to make Tuist feel more like Supabase—something you can set up yourself if you're just getting started and that grows with you all the way up to global development teams with agents helping from their coding environments.